Alfred and the cakes, Cnut and the waves, and Harold Godwinson with an arrow in his eye: Anglo-Saxon history is full of anecdotes. On this blog, I will regularly highlight some amusing and/or remarkable episodes from early medieval England, along with a selfmade cartoon. This post discusses how Eilmer, the flying monk, fell victim to the dangers of reading classical literature.

Studying the Classics in early medieval England

The loss of classical heritage during the Middle Ages is a common misconception. The annotated version of Ovid’s Ars amatoria in the ‘Classbook of St Dunstan’, as well as other annotated Anglo-Saxon manuscripts containing works of such classical authors as Cicero and Cato, demonstrate that classical literature was still being studied in early medieval ‘Dark Age’ England.

Be that as it may, studying the works of Antiquity was not always encouraged. For instance, Bishop Aldhelm of Sherborne (d. 709) once wrote to his student Wihtfrid:

What, think you, does it profit a true believe to inquire busily into the foul love of Proserpina … to desire to learn of Hermione and her various betrothals, to write in epic style the ritual of Priapus and the Luperci? Beware, my son, of evil women and their loves in legend. (Cited in Hunter 1976, p. 41)

Indeed, it is not hard to imagine why Aldhelm doubted the worth of stories about rape (Proserpina), multiple betrothals (Hermione), a fertility god with an oversized, permanently erect penis (Priapus) and a ritual where naked men slap women with goat-skins (the Lupercalia).

Ælfric and the Roman pantheon

The Roman pantheon was also known to the Anglo-Saxons. In his sermon ‘De Falsis Diis’ [On the False Gods], Ælfric of Eynsham (d. c. 1010) describes the Roman gods as strange men and women, obsessed with lust and violence. Venus, in particular, got a damning appraisal:

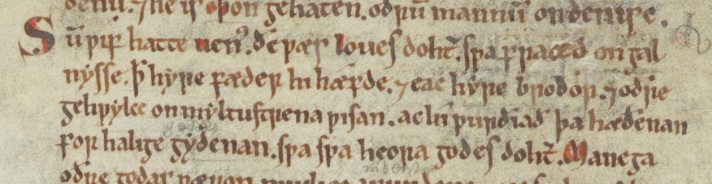

Sum wif hatte Venus, ðe wæs Ioues dohter, swa fraced on galnysse þæt hyre fæder hi hæfde, 7 eac hyre broðor, 7 oðre gehwylce, on myltustrena wisan; ac hi wurðiað þa hæðenan for halige gydenan, swa swa heora godes dohter

[A certain woman was called Venus, she was Jupiter’s daughter, she was so lost in her horniness that her father, and her brother, and many others, had her in the manner of a whore; but the heathens worship her like a holy goddes, as a daughter of their god].

According to Ælfric and his contemporaries, classical mythology was made up by the devil to lure the ignorant souls onto the path of sinfulness.

Eilmer, the flying monk, and the dangers of classical mythology

That studying classical mythology could indeed be risky business is evident from the marvelous tale of Eilmer, the flying monk. Eilmer lived in a monastery in Malmesbury in the 11th century; as a young monk, he became inspired by the story of Daedalus and Icarus. His story is recorded by William of Malmesbury in his Gesta regum Anglorum:

He [Eilmer] was a man learned for those times, of ripe old age, and in his early youth had hazarded a deed of remarkable boldness. He had by some means, I scarcely know what, fastened wings to his hands and feet so that, mistaking fable for truth, he might fly like Daedalus, and, collecting the breeze upon the summit of a tower, flew for more than a furlong [201 metres]. But agitated by the violence of the wind and the swirling of air, as well as by the awareness of his rash attempt, he fell, broke both his legs and was lame ever after. He used to relate as the cause of his failure, his forgetting to provide himself a tail. (source quote)

If you liked this post, you may also enjoy:

- An Anglo-Saxon Anecdote: Cnut the Great and the walking dead

- An Anglo-Saxon Anecdote: A singing ox, some dead pigeons and Saint Edith of Wilton

- An Anglo-Saxon Anecdote: How a peasant beheaded himself

- An Anglo-Saxon Anecdote: Dreaming of witch-wives, fiery pitchforks and the Battle of Fulford

- An Anglo-Saxon Anecdote: The Battle of the Birds, 671

- An Anglo-Saxon Anecdote: How beer and bees beat the Viking siege of Chester in c. 907

- An Anglo-Saxon Anecdote: Earl Siward and the Proper Ways to Die

- An Anglo-Saxon Anecdote: The Real Night of the Long Knives

- An Anglo-Saxon Anecdote: How Hengest was led by the nose

- An Anglo-Saxon Anecdote: Alleluia, the Anglo-Saxon Boo!

Stay tuned (and follow this blog) for more illustrated Anglo-Saxon anecdotes in the future!

Works referred to:

- Michael Hunter, ‘Germanic and Roman antiquity and the sense of the past in Anglo-Saxon England,’ Anglo-Saxon England 3 (1975), 29-50.

Tut, such a slight omission. Who knows how high he would have zoomed with a tail stuck on his posterior?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very amusing. I like your bemused crow.

LikeLiked by 1 person