Beheading is a spectacular way of punishing one’s enemies and often triggers the literary imagination, ranging from Beowulf cutting off Grendel’s head to the Queen of Hearts’s famous phrase “Off with her head!”. This blog post calls attention to the beheadings of three Anglo-Saxons, whose decapitation stories may have been embellished by later generations.

1) The beheading of Æthelberht of East Anglia: The head that tripped up a blind man

“Her Offa Myrcna cyning het Æþelbryhte þæt heafod ofaslean”

[In this year, King Offa of the Mercians commanded Æthelberht’s head to be cut off.]

The annal for the year 794 in The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is straightforward but leaves much to the imagination. What exactly were the circumstances of this decapitation of Æthelberht of East Anglia? In 2014, the finding of a coin bearing Æthelberht’s name and the title “rex” appeared to hold the answer: Æthelberht had claimed independence, to the annoyance of the much more powerful ruler Offa, who had him decapitated (see news article here). Medieval authors came up with more inventive motives for the murder of Æthelberht…

The anonymous author of the twelfth-century Latin Vitae Offarum Duorum (The Lives of Two Offas), for instance, attributed the beheading not to Offa, but to Offa’s scheming wife Cwenthryth. Æthelberht, according to this story, was to marry Offa’s daughter, but Cwenthyrth did not agree and plotted to have Æthelberht murdered. Her plan involved an elaborate boobytrap:

And next to the royal couch she also had a seat prepared, fashioned in the most elegant style and surrounded with curtains on every side. Under which a deep trench was prepared for the heinous plan to be carried through. […] And when he [Æthelberht] settled on the aforesaid seat, he collapsed together with the chair into the bottom of the trench. (trans. Swanton, p. 94-96)

Inside the trench, Cwenthryth’s henchmen were waiting: they suffocated Æthelberht with pillows and stabbed him to death. Since the dead body was still throbbing, they also cut off his head. Thus, Æthelberht, according to the author, died like John the Baptist, “entangled in a woman’s snares”.

Like John the Baptist, Æthelberht became a saint. The anonymous author of the Vitae Offarum Duorum notes how, when Æthelberht’s bodily remains were hurriedly hidden during the night, the head was accidentally dropped onto the ground and left there. By divine providence, a blind man stumbled upon the head:

Finding the aforesaid head a stumbling block to the feet however, he wondered what it was, because his foot was tangled up in the head’s long golden curls. And touching it more carefully, he realised that it was the head of a decapitated man. And intuitively he realised that this was the head of someone holy, and a young man. And when his hands had been steeped in blood, and sometimes in the place where his eyes had been, he put the blood on his face. And immediately his sight was restored. (trans. Swanton, pp. 96, 98)

And that’s how Æthelberht was proven to be a saint: his head tripped up a blind man; the blind man used his blood for face-paint and had his sight restored. Amen!

2) The beheading of St Edmund: The head that kept on shouting

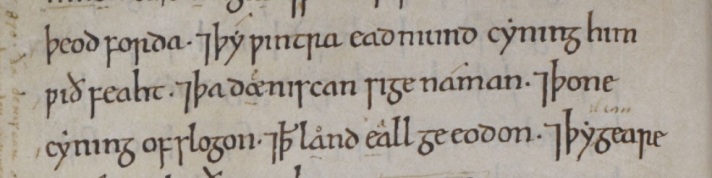

7 þy wintra Eadmund cyning him wið feaht, 7 þa Daniscan sige namon, 7 þone cyning ofslogon

[and that winter King Edmund fought against them and the Danes took the victory and killed the king]

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle‘s report of the death of Edmund of East Anglia is once more devoid of detail. The story of Edmund’s death was later greatly expanded. The Anglo-Saxon abbot and homilist Ælfric (d. c. 1010), for instance, composed an Old English saint’s life (based on a Latin original by the monk Abbo of Fleury), in which he described how the Vikings brutally martyred Edmund. In Ælfric’s version of the events, Edmund does not fight the Danes but lays down his weapons and lets the Vikings have their way with him. The pagans began by using Edmund for target practice, shooting him so full of arrows that Edmund resembled a hedgehog (“swilce igles brysta” [like the bristles of a hedgehog]). Next, they struck off the king’s head and hid it in the bramble bushes:

The Vikings then returned to their ships and departed. Some time later, Edmund’s people return and find their king’s headless body. They start to search for the head and that is when a miracle happens:

Hi eodon þa secende and symle clypigende, swa swa hit gewunelic is þam ðe on wuda gað oft: “Hwær eart þu nu gefera?” And him andwyrde þæt heafod, “Her, her, her!” and swa gelome clypode andswarigende him eallum, swa oft swa heora ænig clypode, oþþæt hi ealle becomen þurh ða clypunga him to.

[Then they went looking and continually calling, as is customary with those who often go into the woods, “Where are you now, friend?” and the head answered them, “Here! Here! Here!” and so frequently called out, answering them all as often as any of them shouted, so that they all came to it because of the shouting”] (ed. and trans. Treharne, pp. 149-151)

They find the head, guarded by a wolf, and bury the head alongside Edmund’s body.

Edmund’s capital miracles do not end there. Ælfric relates how, when they dig up Edmund’s body and head some years later, they find that the head has been reattached: God works in mysterious ways, indeed!

3) The beheading of Earl Byrhtnoth: The head that was stolen by Vikings

Her wæs Gypeswic gehergod, 7 æfter þæm swyðe raþe wæs Byrihtnoð ealdorman ofslagan æt Meldune.

[In this year, Ipswich was ravished, and very soon after that Ealdorman Byrhtnoth was killed at Maldon].

Annal 991 of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle contains another bare report on the death of Anglo-Saxon. For more details about the death of Byrhtnoth we need to look elsewhere. The anonymous author of one of the greatest poems in Old English, The Battle of Maldon, elaborated on how Byrhtnoth and his men heroically (or: foolishly) fought the Vikings on the beach of Maldon, after yielding them free passage over a narrow causeway (see The Battle of Maldon: A Student Doodle Edition). In the poem, Byrhtnoth is struck fatally by a spear in the chest and dies uttering some final words of inspiration to his retainers.

The twelfth-century Liber Eliensis tells a different story, indicating that Byrhtnoth was, in fact, beheaded by the Vikings:

On the last day, and with few of his men left, Brithnoth knew he was going to die, but this did not lessen his efforts against the enemy. Having inflicted an enormous slaughter on the Danes, he almost put them to flight. But eventually the enemy took comfort from the small number of Brithnoth’s men, and, forming themselves into a wedge, rushed against him in one body. After an enormous effort the Danes barely managed to cut off Brithnoth’s head as he fought. They carried the head away with them and fled to their own land. (trans. Calder & Allan, p. 190)

The Liber Eliensis also reports that the abbot of Ely went to the battlefield to collect the remains of Byrhtnoth and buried the headless body in Ely Abbey, replacing the head with a lump of wax: “But in place of the head he put a round ball of wax, by which sign the body was recognized long afterwards in our own times and placed with honor among the others” (trans Calder & Allan, p. 192). The Liber Eliensis‘s reference to the placement of Byrhtnoth’s remains “among the others” is to a twelfth-century shrine of the seven benefactors of Ely Abbey, which is now found in Ely Cathedral:

Did the Vikings indeed steal Byrhnoth’s head or is this another case of literary embellishment? Judging by a report of how the bones of the seven Ely benefactors were uncovered in May 1769, it seems that this legend has a ring of truth to it:

Whether their relics were still to be found was uncertain … The bones were found inclosed, in seven distinct cells or cavities, each twenty-two inches in length, seven broad, and eighteen deep, made within the wall under their painted effigies; but in that under Duke Brithnoth there were no remains of the head, though we search diligently …It was observed that the collar bone had been nearly cut through, as by a battle axe or two-handed sword. (James Bentham to the Dean of Exeter; cit. in Stubbs, pp. 92-93)

If the Vikings did indeed behead Byrhtnoth, this raises the question of why the anonymous poet of The Battle of Maldon did not include this detail in his poem; perhaps he considered it ‘fake news’.

If you liked this blog post, you may also be interested in:

- An Anglo-Saxon Anecdote: How a peasant beheaded himself

- An Anglo-Saxon Anecdote: Earl Siward and the Proper Ways to Die

Works referred to:

- Calder, D. G., & M. J. B. Allen, Sources and Analogues of Old English Poetry (London, 1976)

- Stubbs, C. W., Historical Memorials of Ely Cathedral (New York, 1897)

- Swanton, M. (Trans.), The Lives of Two Offas (Crediton, 2010)

- Treharne, E., Old and Middle English c. 890-c.1450: An Anthology, 3rd edn. (Malden, 2010)

Bonus bunny

One thought on “Chop chop! Three bizarre beheadings in Anglo-Saxon England”