The newly elected president of the United States has triggered over half a million women to march in a political protest against the new leader of their country. While this Women’s March was record-breaking, a report in an eleventh-century manuscript of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle suggests that it may not have been unprecedented. This is the story of Gytha and the Anglo-Saxon rebellion against William the Conqueror. #NotMyConqueror

A Women’s March to Flat Holm in 1068

The entry for the year 1067 in manuscript D of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes a number of events that took place in the two years following the Norman Conquest in 1066. Most of the executive orders by the new king William are described in a rather negative manner, such as his imposing a heavy tax on the “earm folc” [poor people] and his siege of Exeter in 1068 (“he heom wel behet, 7 yfele gelæste” [he promised them well and he performed evil]). The annalist is more positive about a curious journey by Gytha, mother of the deceased King Harold Godwinson (d. 1066), who was joined by other women of good standing:

7 her ferde Gyða ut, Haroldes modor, 7 manegra godra manna wif mid hyre, into Bradan Reolice, 7 þær wunode sume hwile, 7 swa for þanon ofer sæ to Sancte Audomare.

[and in this year Gytha, Harold’s mother, went out and many wives of good men with her, to Flat Holme, and remained there for a while and thus from there over sea to St Omer (France)]

Gytha’s ‘Women’s March’ is part of the English rebellion against William the Conqueror and probably followed the Siege of Exeter in 1068, in which Gytha played an important role.

Gytha and her sons: Breaking their mother’s heart three times over.

Much of what we know about Gytha (fl. 1022-1068) derives from sources post-dating the Norman Conquest. According to the Domesday Book, she was one of the greatest women landowners in the year 1066 (Stafford 1989), She owed much of her wealth and status to her marriage to the powerful Earl Godwin of Wessex (d. 1053), whom she bore many sons and daughters. Most of her sons became powerful earls and one of them even became king in 1066 (Harold Godwinson). While their careers may have made Gytha proud, some of her sons’ actions may have broken her heart.

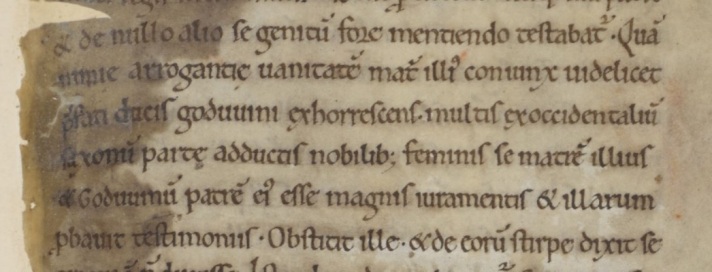

Sweyn Godwinson, earl of Herefordshire (d. 1058), for instance, shocked his mother by insisting that Godwin was not his real father. Instead, he claimed to be the son of Cnut the Great (d. 1035). Sweyn’s claim was recorded in the late eleventh-century Cartulary of Hemming (a collection of charters and lawsuits regarding lands in Worcester). Hemming also included Gytha’s reaction:

Quam nimie arrogantie vanitatem mater illius, conjunx videlicet prefati ducis Godwini, exhorrescens, multis ex occidentalium Saxonum parte adductis nobilibus feminis, se matrem illius, et Godwinum patrem ejus esse, magnis juramentis et illarum probavit testmoniis.

[His mother, the wife of the aforesaid Earl Godwin, horrified by his excessive arrogance and vanity, brought together many noble ladies from the West Saxons, and proved by great oaths and their testimony that she was his mother and Godwine was his father.]

Sweyn disagreed and Hemming reports that while Cnut and Sweyn may not have shared blood and genes, they did share certain shortcomings, such as pride and excessive lusts of the flesh. To illustrate the latter, Hemming narrates how Sweyn had once abducted the abbess of Leominster and had kept her as a wife for a year. He had returned the abbess after threats of excommunication by the bishop of Worcester but had then retaliated by stealing some estates from the diocese of Worcester. Clearly the black sheep of the family, Sweyn was exiled on various occasions and died in 1052 after returning from a penitential pilgrimage to the Holy Land – Sweyn certainly did not make his mommy proud!

Her two more famous sons, Tostig (d. 1066) and Harold, did little better. In the year of the Norman Conquest, Tostig had rebelled against the English throne and had sided with the Norwegian king Harald Hardrada (d. 1066). In the Battle at Stamford Bridge, brother fought brother and Tostig was killed. Following the battle and his brother’s death, Harold hears the news that the Norman fleet of William has landed and Harold wants to rush south. The chronicler Orderic Vitalis (d. c. 1142) writes how Gytha, having just lost Tostig, feared for Harold’s life and tried to dissuade her son. Harold not only refused to listen to his elderly mother, he gave her a kick to boot: “[Harold] even forgot himself so far as to kick his mother when she hung about him in her too great anxiety to detain him with her” (trans. Forester, Vol. I, p. 482). Ouch!

Gytha’s fear became a reality and Harold did die at the Battle of Hastings. Orderic Vitalis reports how the grieving mother had asked William the Conqueror for the body of her son:

The sorrowing mother now offered to Duke William, for the body of Harold, its weight in gold; but the great conqueror refused such a barter, thinking it was not right that a mother should pay the last honours to one by whose insatiable ambition vast numbers lay unburied (trans. Forester, Vol. I, p. 488)

Another twelfth-century chronicler, William of Malmesbury (d. c. 1143) supplies an ‘alternative fact’: “He sent the body of Harold to his mother, who begged it, unransomed; though she proffered large sums by her messengers” (trans. Giles, pp. 280-281).

Whatever may have happened to Harold’s body, Gytha had every reason to detest William and she, a well-connected and wealthy noblewoman, became the focal point of resistance against the new Norman overlord.

Gytha and the Siege of Exeter in 1068

It is generally assumed that Gytha was involved in the resistance offered by the city of Exeter in 1068. Orderic Vitalis records how Exeter was the first city to fight for its freedom. The townsfolk barricaded the city walls and claimed “We will neither swear allegiance to the king, nor admit him within our walls; but will pay him tribute, according to ancient custom” (trans. Forester, Vol. II, p. 15). #NotMyConqueror. William gathered 500 horsemen and marched on Exeter. He besieged the town for eighteen days and committed various acts of cruelty, including the blinding of one the hostages. William of Malmesbury related William’s ferocity to an intriguing action by one of the Exeter townsfolk:

Indeed he had attacked it with more ferocity, asserting that those irreverent men would be deserted by God’s favour, because one of them, standing upon the wall, had bared his posteriors, and had broken wind, in contempt of the Normans. (trans. Giles, p. 282)

That’s right, it seems as if someone farted in the king’s general direction! After eighteen days, Exeter capitulated, but Gytha had escaped and began making her way to Flat Holm.

A Women’s March or a Women’s Flight?

The Siege of Exeter was a definite blow to Gytha and her rebellion. However, her march might still be regarded as an act of defiance against William, if only because a group of travelling noblewomen was sure to draw the people’s attention. It certainly made an impression on the annalist of annal 1067 in MS D of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Whereas he had denounced William’s actions following the Norman Conquest (see above), the annalist writes approvingly of Gytha’s going out, noting how the women who joined her are the “wives of good men”. Orderic Vitalis, generally more appreciative of William the Conqueror, is more negative about Gytha’s retreat to France. After going over how various English uprisings were justly put to rest, Orderic describes how Gytha “secretly collected vast wealth, and from her fear of King William crossed over to France, never to return” (trans. Forester, Vol. II, pp. 23-24).

So, was it a women’s march or a women’s flight? Much depends, it would seem, on the political stance of the person bringing the news – a notion that still very much applies to this day and age.

If you liked this blog post, you may also be interested in:

- Lǣce Hwā: Doctor Who and the Norman Conquest

- An Anglo-Saxon Anecdote: Dreaming of witch-wives, fiery pitchforks and the Battle of Fulford

- Anglo-Saxon bynames: Old English nicknames from the Domesday Book

Works referred to:

- Stafford, Pauline, ‘Women in Domesday’, Reading Medieval Studies 15 (1989), 75-94

- Forester, T. A. (Trans.), The Ecclesiastical History of England and Normandy by Orderic Vitalis (London, 1853-1854)

- Giles, J.A. (Trans.), William of Malmesbury’s Chronicle of the English Kings (London, 1847)

Interesting and topical. I had not heard about Gytha’s ‘march’ before. From the source evidence it is difficult to understand whether these women were marching or just fleeing. The latter would make more sense as she must have feared that William would take her lands and wealth for himself and it seemed more prudent to seek exile in France. Did she have relatives there who could offer her protection or did she flee to a nunnery? Did she seek to gather people to her as she moved across the country, as an act of defiance, or was she travelling with an escort of noble women?

LikeLike

A long sea journey from Flat Holm to St Omer… or did she come ashore and travel by land to the south coast and get a passage from there?If our house was one floor taller we could see Flat Holm from our windows!

LikeLike