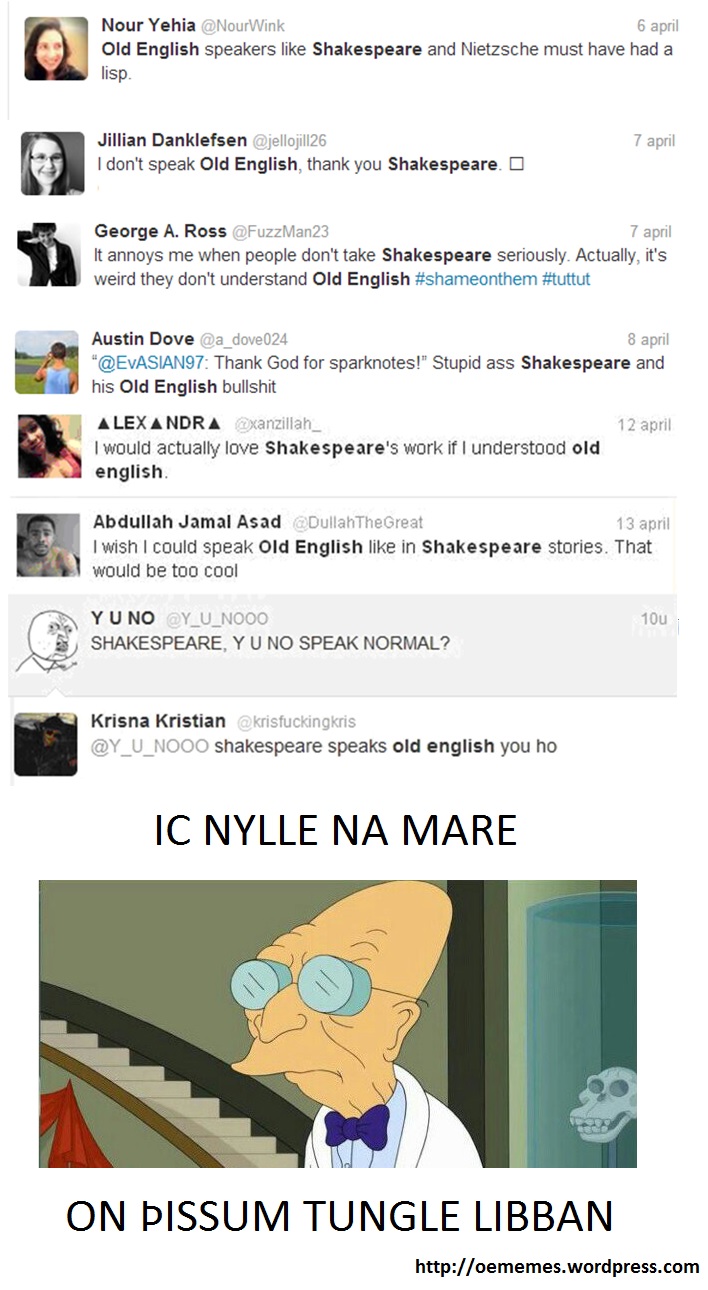

Whenever I tell people I study and teach Old English, they react by feeding me their favourite lines of Shakespeare, noting that it is very difficult indeed: “Is this a dagger I see before me? Alas, poor Yorick! Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?”. Indeed, as a little search on Twitter (see the image at the bottom of this post) indicates, the association between William Shakespeare (1564-1616) and Old English (ca 45o-1100) is a widespread myth that deserves to be busted. What better way to do so, than to imagine what it would look like if William Shakespeare HAD written Old English? This blog features my own very first translation of one of Shakespeare’s sonnets into Old English.

Shakespeare’s ‘Sonnet 18’ in Old English

Sceal ic þē gelīcian tō sumeres dæge?

Þū eart luflīcra ond staþolfæstra.

Rūge windas sceacað þrīmilces dȳrlinge blōstman

Ond sumeres lǣn hæfð eall tō lȳtelne termen.

Hwīlum heofones eage tō hāte scīnð,

Ond oft his gylden hīw is dimmod;

Ond ælc þāra fægernese hwīlum unwlitegað,

Of belimpe oþþe gesceaftes wendendum pæðe ne geglenged;

Ac þīn ēce sumor ne sceall forweornian

Ne forleosan þā fægernese þe þū hæfð;

Ne Dēaþ hrēman ne þorfte þæt þū wandrast in his sceadwe,

Þonne þū in ēce linan tō tīde grēwst

Swā lange swā man mæg orþian oþþe eagan magon sēon,

Swā lange swā þes lifaþ, ond þes þē līf giefþ.

You can find the original text of the sonnet and an analysis of its contents here.

William Shakespeare did not write Old English

As the above translation of sonnet 18 makes clear, Old English is rather different from the English used by Shakespeare. We might note, first of all, a number of different letters: the ‘æ’ to represent the sound in Modern English cat and the ‘þ’ and ‘ð’ that are used interchangeably to represent the first sound in thorn. The use of the macrons above the vowels are a modern convention to indicate long vowels. Another difference includes the spelling of words: with some imagination we can recognize the phrases ‘a summer’s day’ and ‘rough winds’ in ‘sumeres dæge’ and ‘rūge windas’. Furthermore, in his original sonnet Shakespeare used words that were not available in Old English, such as ‘compare’ and ‘complexion’ which were introduced in the later Middle Ages, out of French – the Anglo-Saxons would have used ‘gelīcian’ and ‘hīw’ instead. I particularly like the word ‘þrīmilc’ for ‘May’; the Old English word, which translates to ‘three-milk’, reflects the fact that, in May, you can milk your cows three times a day! Other differences include the more extensive use of inflectional endings in Old English (which still had forms for the genitive, accusative and dative) and word order. In short, the English that Shakespeare used for his ‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day’ is NOT Old English.

William Shakespeare did not write Present-Day English

While it is obviously silly to claim that Shakespeare wrote Old English, it is equally ridiculous to assume that he used the same English that we do today. Two examples will suffice to illustrate this idea. The ‘weird sisters’ in Shakespeare’s MacBeth are often portrayed as odd and strange little women, wobbling about awkwardly and screaming and snorting like lunatics. The nature of their portrayal might be derived from the fact that the word weird today means ‘strange, unusual’. However, it is worth noting that this sense of the word is only attested from the 19th century onwards (see the entry for weird in the OED). In Shakespeare’s time, weird meant ‘Having the power to control the fate or destiny of human beings, etc.’. In other words, Shakespeare used the word in a sense that is more closely connected to Old English wyrd ‘fate’, than it is to Modern English weird ‘strange, unusual’. A second example that illustrates that we must not confuse Shakespeare’s English with our own is championed by the linguist David Crystal and his son Ben, an actor. They argue that if we pronounce Shakespeare’s work as we would Present-day English, we miss out on a lot of puns. For instance, the words ‘hour’ and ‘whore’ sounded alike in Shakespeare’s time, giving the line ‘From hour to hour we ripe and ripe’ (As you like it, act 2, scene 7) a slightly humourous air – especially since ‘ripe’ and ‘rape’ would also have been homonyms. You can view the Crystals’ plea here.

To conclude, when it comes to reading English texts from the past, it seems as if Shakespeare’s adage ‘to thine own self be true’ should be taken into account: read Shakespeare as if he wrote Early Modern English and, please, do not confuse this with its more beautiful ancestor, Old English.

rape and ripe would not have been homophones for Shakespeare. ripe would have been [reip]and rape would have been [ra:p]. At least these are the values that you’d get for these categories (southern ME /i:/ and /a:/ according to the best of the contemporary phoneticians, John Hart (An orthographie, 1569).

LikeLike

brilliant, thanks so much!

LikeLike

That was wonderful! I would love to hear more.

LikeLike

brilliant! Þa begoten þe ic swa swa joste þa riht!.Ic beo þa wonderlicu gehieran!😁

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Scholarly Scribe.

LikeLike

We miss a lot of Shakespeare’s meaning and craft because we pronounce the words differently today. See: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/theatre/william-shakespeare/10372964/Shakespeare-read-in-Elizabethan-accent-reveals-puns-jokes-and-rhymes.html

LikeLike