The second episode of The Last Kingdom (UK airdate: Thursday, 29 October, 9 pm, BBC 2) introduces Prince Alfred, who would later become King Alfred the Great (d. 899). In his first scene, Alfred is portrayed as a man tormented both physically (because of his health) and morally (because of his lustful feelings towards the flustered maidservant that had just left his room). This blog post highlights some sources related to the historical Alfred and explores what they reveal about his passions…and his piles.

Alfred the Great (849-899): An unlikely king, a sickly sovereign

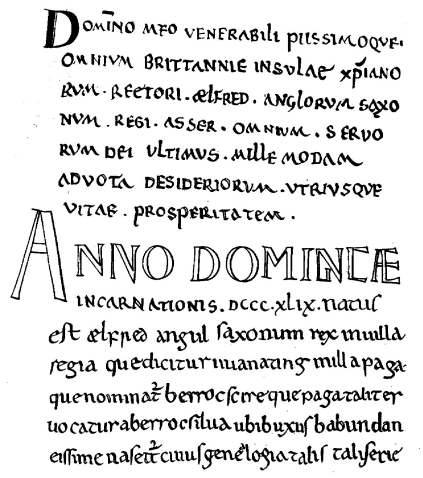

Known as one of the greatest monarchs of Anglo-Saxon history, defeater of the Danes and instigator of an important educational reform, Alfred was, in fact, an unlikely candidate for the throne of Wessex. For one, he was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf of Wessex (reign 839-858), which means he had four older brothers: Æthelstan (d. 852), Æthelred (King of Wessex, 858-860), Æthelbald (King of Wessex, 860-865) and Æthelberht (King of Wessex, 865-871). Only after all his brothers had died, Alfred (apparently, Æthelwulf had run out of Æthel-names…) became eligible to rule. Given that he was the youngest of five, Alfred was probably groomed for an ecclesiastical career (his father took him to see the pope, twice), which may explain his interests in learning in his later life. Another reason why Alfred may have been considered an unlikely king at the time was because he suffered from a terrible illness, as is revealed by a biography written during his life by Bishop Asser in the year 893.

Be careful what you wish for!

Asser’s Life of King Alfred is a unique source on Alfred’s life and character, written by one of his own courtiers. Asser not only records Alfred’s battles with the Vikings and his dealings at court, he also reports some of Alfred’s medical details, mentioning that, from his youth, Alfred had suffered from “ficus” [piles, haemeroids].

Interestingly, Asser also tells us how Alfred acquired his piles in his early days:

when he [Alfred] realized that he was unable to abstain from carnal desire, fearing he would incur god’s disfavour if he did anything contrary to His will … [he would pray] that Almighty God through His mercy would more staunchly strengthen his resolve in the love of His service by means of some illness which he would be able to tolerate … when he had done this frequently with great mental devotion, after some time he contracted the disease of piles through God’s gift. (Asser, Life of King Alfred, ch. 74)

In other words, young Alfred, afraid of his own dirty thoughts, asked God to grant him a distraction and God gave him haemeroids!

Out of the frying pan, into the fire: “A sudden severe pain that was quite unknown to all physicians”

Asser’s biography also records that Alfred was miraculously cured from his piles when , prior to his wedding, Alfred had asked God to “substitute for the pangs of the present and agonizing infirmity some less severe illness” (Asser, Life of King Alfred, ch. 74). The young prince was miraculously cured: hurray! His regained health would be short-lived, however, since he suddenly fell ill on his wedding night: he had been struck by an illness that proved incurable. This new disease would torment him the rest of his life, as Asser noted:

he has been plagued continually with the savage attacks of some unknown disease, such that he does not have even a single hour of peace in which he does not either suffer from the disease itself or else, gloomily dreading it, is not driven almost to despair. (Asser, Life of King Alfred, ch. 91)

While the disease may have been unknown to the Anglo-Saxon physicians, modern-day scholars have used Asser’s description to diagnose Alfred with Crohn’s disease (Craig 1991). This diagnosis is corroborated by another document made during Alfred’s lifetime: Bald’s Leechbook.

Bald’s Leechbook is a compilation of various medical texts, which was possibly made at Alfred’s own request. Within this compilation, there is a section that is concluded by “þis eal het þus secgan ælfrede cyninge domine helias patriarcha on gerusalem” [Elias, the patriarch of Jerusalem (c. 879-907), ordered all of this to be told to King Alfred]. Included in this section are remedies for the alleviation of constipation, diarrhoea, pain in the spleen and internal tenderness, which all fit well with the pathology of Crohn’s disease(Craig 1991, p. 304). The Old English text also records that Elias sent him a “hwita stan” [a white stone], which could be used against all sorts of illnesses; as an added bonus, the white stone would also protect the owner from lightning and thunders (the text is edited by Cockayne 1864, Vol. II, pp. 288-291).

To make a long story short: Alfred was a passionate boy, God gave him piles and the patriarch of Jerusalem gave him a pebble. Poor Alfred.

If you liked this post, why not follow this blog for regular updates and/or read the following blog posts about Alfred the Great:

- The Illustrated Psalms of Alfred the Great: The Old English Paris Psalter

- Lǣce Hwā: Doctor Who and Alfred the Great

- Arseling: A Word Coined by Alfred the Great?

Works refered to:

- Asser, Life of King Alfred, trans. S. Keynes and M. Lapidge (Harmondsworth, 1983)

- Cockayne, T. O. (ed.), Leechdoms, wortcunning, and starcraft of early England (London, 1846; available here)

- Craig, G., ‘Alfred the Great: A Diagnosis’, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 84 (1991), 303-305.

5 thoughts on “Passion, Piles and a Pebble: What Ailed Alfred the Great?”